Understanding Teen Sleep Behavior

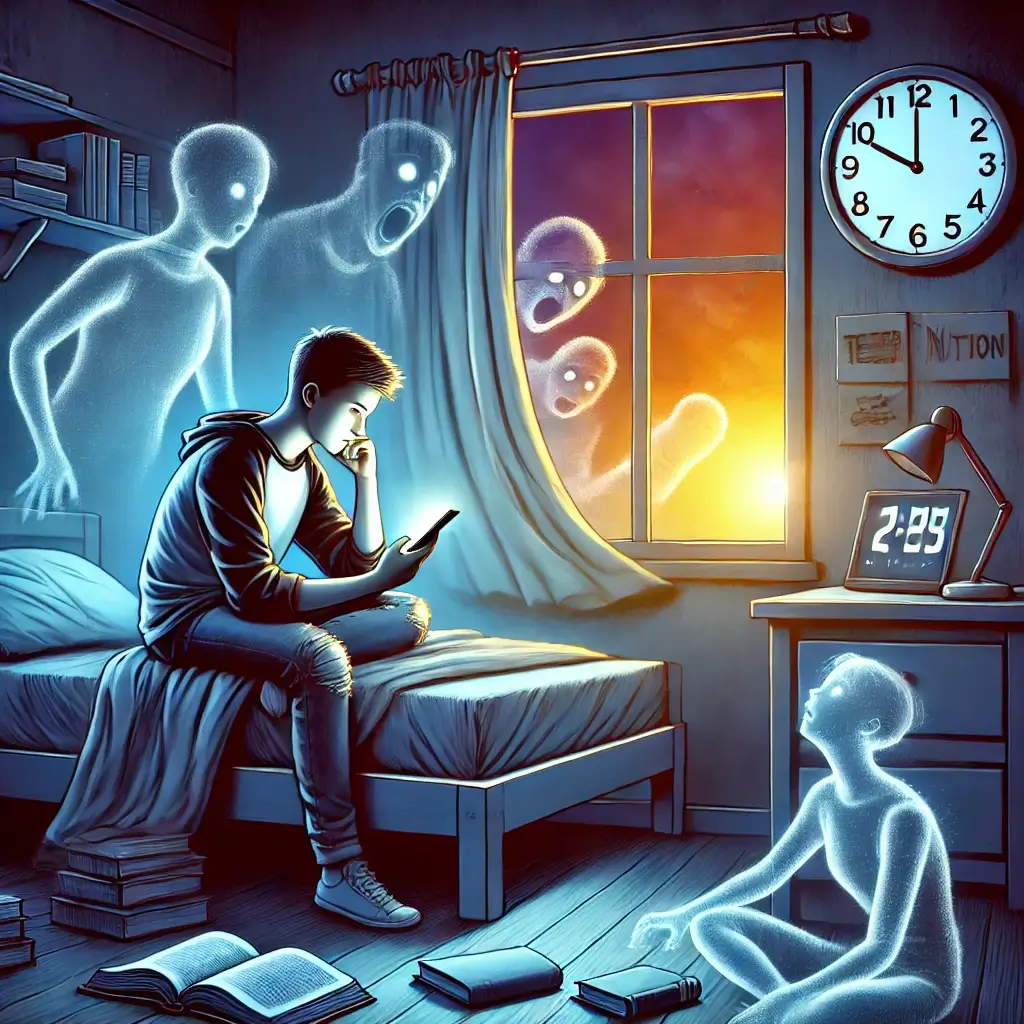

Teenagers’ late-night habits often perplex parents and educators alike. Why do adolescents seem biologically programmed to stay up late, often at the expense of sufficient sleep? This pattern is not merely a reflection of choice or rebellion but a natural outcome of biological, developmental, and social factors that shape adolescent behavior.

During adolescence, the internal clock that governs the body’s sleep-wake cycle undergoes a shift, leading to delayed sleep onset and a preference for late-night activity. Coupled with societal pressures such as early school start times and digital engagement, teenagers face a chronic sleep deficit. This deficit significantly impacts their mental and physical health, academic performance, and overall well-being.

Understanding the Research Context

This article examines the intricate interplay of biological changes, societal challenges, and technological distractions contributing to adolescent sleep deprivation. By integrating evidence-based research with practical strategies, it offers a roadmap for navigating these challenges and promoting healthier sleep patterns in teenagers.

The Biology of Adolescent Sleep Patterns

The circadian rhythm, or the body’s internal clock, dictates the timing of sleep and wakefulness. In teenagers, this rhythm shifts during puberty, delaying melatonin release by up to two hours. This biological change, known as a sleep phase delay, is universal across cultures and species, signifying its evolutionary importance. However, it conflicts with traditional societal schedules, particularly early school start times.

Brain Development and Sleep

The teenage brain undergoes significant remodeling during adolescence, particularly in the prefrontal cortex responsible for decision-making and impulse control. This underdevelopment can lead to poor sleep-related decisions, such as staying up late to socialize or engage with digital media, despite knowing the importance of rest.

Hormonal Influences on Sleep Patterns

In addition to melatonin shifts, hormonal fluctuations during adolescence contribute to heightened energy levels in the evening. This explains why many teens experience a “second wind” late at night, making it even harder to wind down and prepare for bed.

Social and Digital Connection Impact

Adolescents’ social lives are pivotal to their identity formation and emotional health. Late-night texting, gaming, and video chatting have become commonplace among teenagers seeking connection in the digital age. While these activities fulfill their need for social interaction, they often extend well into the night, delaying bedtime and reducing total sleep duration.

Screen Time and Sleep Quality

Exposure to screens—smartphones, tablets, and computers—at night suppresses melatonin production due to blue light emission from electronic devices. Studies show that adolescents who use electronic devices before bed take longer to fall asleep and report poorer sleep quality. This screen-induced disruption exacerbates the already challenging sleep phase delay.

Academic Pressure and Sleep Deprivation

With increasing academic demands, many teens sacrifice sleep to complete homework or prepare for exams. A survey by the National Sleep Foundation revealed that nearly 70% of high school students get fewer than eight hours of sleep on school nights, falling short of the recommended 8–10 hours.

Health Impact of Sleep Deprivation

Chronic sleep deprivation has a domino effect, impacting multiple facets of a teenager’s life. Sleep-deprived teens perform worse on tasks requiring attention and problem-solving. Insufficient sleep is strongly linked to mood disorders, including depression and anxiety. Adolescents who sleep fewer than six hours a night are twice as likely to exhibit depressive symptoms.

Solutions for Better Sleep

Advocacy for later school start times has gained momentum in recent years. Studies show that delaying start times by even 30 minutes can significantly improve sleep duration and academic performance. Encouraging consistent sleep schedules, limiting caffeine intake, and creating a tech-free bedtime routine can help teenagers improve sleep quality.

Educational Approaches

Open communication about the benefits of sleep and its impact on academic and emotional well-being can empower teens to prioritize rest. Morning sunlight exposure helps regulate the circadian rhythm, encouraging earlier bedtimes and better overall sleep patterns.

Moving Forward

Teenagers’ late-night habits are rooted in a combination of biology, societal expectations, and personal choices. Understanding the scientific basis for these behaviors is critical for fostering empathy and collaboration between teens, parents, and educators. By combining practical strategies with systemic changes, such as advocating for later school start times, society can support adolescents in achieving the restorative sleep they need to thrive.

References

Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., & Jenni, O. G. (1993). Regulation of adolescent sleep: Implications for behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021, 276–291.

Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(4), 1232–1237.

Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., et al. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40–43.

Lo, J. C., Ong, J. L., Leong, R. L., Gooley, J. J., & Chee, M. W. (2016). Cognitive performance during sleep deprivation: The role of working memory capacity. Sleep Medicine, 24, 40–48.

Roberts, R. E., Roberts, C. R., & Duong, H. T. (2014). Sleepless in adolescence: Prospective data on sleep deprivation, health, and functioning. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(6), 692–697.